“A way and a means of striking a root through the ‘narrow gate’ in the depth of the soul out into the domain of the pure arid un-imprisonable Spirit which itself opens out onto the Divinity.” That is how Ahmad Al Tajani (a revered Sufi born in modern day Algeria) defines Sufism and even though there have been many definitions, this quintessentially addresses the core embodiment of the Sufi philosophy.

Just like art, Sufism knows no bounds. It could be found in the hands of the dervishes in India while also residing with the Alawiyya community in France. Sufism echoes through history and paves the way for a more meaningful future and to aid this ART at its forefronts. It is deep rooted in Sufi philosophy but the most well-known and exalted example would be of Jalal al-Din Rumi.

I died to the mineral state and became a plant,

I died to the vegetal state and reached animality,

I died to the animal state and became a man,

Then what should I fear? I have never become less from dying.

At the next charge (forward) I will die to human nature,

So that I may lift up (my) head and wings (and soar) among the angels,

And I must (also) jump from the river of (the state of) the angel,

Everything perishes except His Face,

Once again I will become sacrificed from (the state of) the angel,

I will become that which cannot come into the imagination,

Then I will become non-existent; non-existence says to me (in tones) like an organ,

Truly, to Him is our return.

Rumi’s work revolves around a common theme of finding oneself through finding God. He wrote many ghazals; his pen and ink being the greatest form of Sufi art to this date. His words, kissed by time, point towards the immortality, the benevolence and the veiled notion of God himself while also enlightening on the idea of dreams and desires as he paints God as one needing no face and as one who only unveils His face and essence to the greatest of His followers.

In India during the 1640s, Muslim devotional art witnessed a radical change under imperial Mughal patronage. Under the direction of their sheikh, Mulla Shah, two of Emperor Shah Jahan’s children joined a Sufi order at this time. The emperor’s favoured daughter, Jahanara Begum, rose to prominence as a major sponsor of Sufism in North India. She commissioned pictures of her lord as well as paintings of contemporary Muslim saints. Before she embraced Sufism, the general imagery of Sufism with Muslim mystics tended to be either metaphorical or historical, frequently created to support the Mughal ideology that their monarchy was divinely destined. Hence, many of these portraits took on a contemplative quality after her introduction. In order to explain the fundamental purpose of devotional portrayals, this article examines the works of three of Mulla Shah’s disciples: Jahanara Begum, her brother Dara Shikoh, and Tavakkul Beg.

Anyone who gazed, with honest devotion, upon the face of Shah

Wheresoever he looked, he saw the face of God

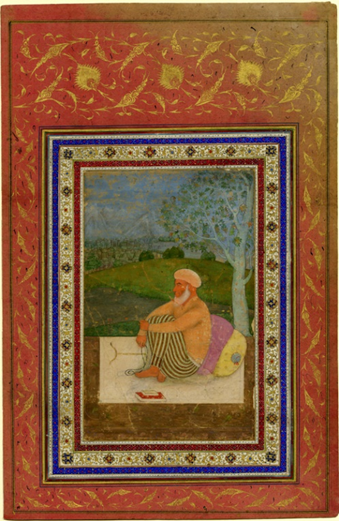

A fascinating depiction of the saint in the British Museum’s collection offers a visual allegory for Tavakkul Beg’s account of Mulla Shah. The saint is seen in the picture sitting on a platform beneath a plane tree while donning his typical white Afghan hat. His Sufi lodge, or khnqh, which was outside of Srinagar, is the setting established. According to Dara Shikoh’s Saknat-ul Awliy (The Tranquility of the Saints), “At present your blessed abode, which is the Ka’ba of seekers and the qibla [place of prayer facing the Ka’ba] for the needy, is located in the middle of the Kashmir Fort on Koh-Hari Hill, which is a very pleasant place with a view of most of the city below.” The sprawling metropolis may be seen in the backdrop, hidden from view by the shadows of the majestic Himalayas, on the shores of Lake Dal. Mulla Shah is seen apart from the bustle of the world, sitting with his legs up and counting beads. The plane tree symbolizes the epitome of his spirituality.

So, for Indian Sufi Art, God was hidden but perhaps in the surroundings of Mulla Shah and it was only in his surroundings that by virtue of his spirituality could you see or feel God. The need to see God was so that even later, Emperor Jahangir was thought to have preferred Sufi saints to kings. We can observe by the features of the paintings and the values ascribed to them that for India and Indian saints, God was hidden in Nature and only revealed Himself in the presence of those who were in sync with nature.

Ney, Oud and Komuz are perhaps the final attempt of the Arabic world to decipher the face of God; for them it exists in melody and music as they reinforce the tradition of Zikr. Singing the praises of their Lord, a Deity that is All knowing, Utterly Just and the All Wise. It is perhaps the Song of the soul. Ghazali, a revered scholar says:

‘What causes mystical states to appear in the heart when listening to music (Sama) is a divine mystery found within the concordant relationship of measured tones (of music) to the (human) spirits and in the spirits becoming overwhelmed by the strains of these melodies and stirred by them – whether to experience longing, joy, grief, expansion or constriction. But knowledge of the cause as to why spirits are affected through sound is one of the mystical subtleties of the science of visionary experience.’

There is no established form of Sufi music; only styles with Turkey and its Whirling Dervish, Pakistan and its Qawali, Morocco and Gnawa – all signaling to perhaps finding God in their own individuality but through the same stream.